Open to buses, taxis, and motorcycles up to 125cc. East footpath open to cyclists and pedestrians. West footpath closed for essential maintenance.

Access RestrictionsDavid Climie

Project DirectorIn the first in a series of fascinating and lively profiles of key personnel from right across the project team, we talk to Transport Scotland’s Project Director David Climie. In an in-depth interview, we find out about a global career full of unique challenges and equally unique solutions.

Around the World in Eight Bridges

There are no ideal CVs in civil engineering. One of its great attractions is the diverse paths people take: the unexpected experiences, unforeseen problems and unconventional solutions you can store away never knowing the minute when they might be applicable on a future job.

So to become project director of the Forth Replacement Crossing, David Climie didn’t necessarily need a globetrotting career building bridges in typhoon zones with the highest profile of geo-political deadlines to meet… or with the President of China breathing down his neck, crossing out the days before the anniversary of the People’s Revolution. He didn’t need to have raced to rebuild the stadium of the world’s oldest professional football club in time for the season kicking off. And he didn’t need to have helped solve communications issues among several multi-national project teams with the aid of a battalion of demobbed British Army Ghurkhas or, that rarest of civil-engineering posts… the on-site cartoonist.

But it all helps.

Climie, who represents the Scottish Government client on the biggest transport project in Scotland for a generation, has many pins in a fascinating career map that so far includes Egypt, Hong Kong, China, Denmark, the United States and, of course, the Firth of Forth (twice). But it might have all been so different if not for one fateful, virtually on-the-spot decision.

David Climie's Eight Bridges...so far:

- Friarton Bridge – young Climie gets bridges bug on visit to site accompanied by family friend

- Kessock Bridge – summer work as engineering student (Heriot Watt)

- Forth Road Bridge – strengthening works

- Tsing Ma Bridge

- Storebaelt Bridge

- Jiangyin Bridge

- Tacoma Narrows Bridge

- Queensferry Crossing

Back in the early 1980s, the young Cleveland Bridge graduate trainee was working in Sunderland on one of his first placements, building the famous Nissan plant in Sunderland, the first Japanese car factory in the UK.

His first recollection is the incessant cold, a biting Siberian wind blasting around the site, the old Sunderland airport.

“I remember thinking if I can survive this, I can survive anything,” he said.

“I’d been there about six months when one lunchtime I got a phone call from head office asking if I’d like to go to Egypt.

“I asked ‘How long for?’

‘Oh a year or so.’

‘When do you want me to go?’

“…this weekend.”

He laughs at the memory, although his younger self was still self-assured enough to ask for another week to think it through. Presumably that Siberian wind whipping off the North Sea and scything down the Wear helped clarify the mind: the following weekend he was on a plane to Cairo as part of a small Cleveland Bridge team sub-contracted to provide steel bridge girders for sections of a new expressway from the centre of the Egyptian capital to the airport.

Looking back, it was a job that set the tone for Climie’s career and his adult life.

“Global travel hadn’t ever really occurred to me up until that point. But it was great when it happened and when it did, I just wanted to keep doing it. I’ve always seen it as part of a broader experience of life and getting paid to work in places you might otherwise never see is great. As long as you go with an open mind and are prepared to assimilate as much as possible. If you want to live like you do in the UK, then it’s not always going to work.”

Experiencing new cultures wasn’t just a matter of different environments and cuisine. The global world of major infrastructure engineering is typically about skilled people from all over the world meeting on jobs where cultures can sometimes clash.

“Egypt was my first experience of different safety cultures, it was very, very different. Without being too blunt about it, the attitude was ‘if someone gets killed, we get someone else’. It was hard to wrap your head around. The consequences of risk just weren’t perceived in the same way there.

“For us, it was a case of making sure our people were safe and doing the best we could to influence others, but we were limited in what we could do.”

Team building across skill, cultural and language barriers is a key theme in his career. As section manager on Hong Kong’s Tsing Ma Bridge works in the mid-1990s, his workforce on suspension cables and deck erection largely comprised semi-skilled Chinese labour. But as luck would have it, the British Army was scaling back from Hong Kong prior to the 1997 handover to China and around 100 Gurkhas were available to draft in as charge hands.

Tsing Ma Bridge, Hong Kong

“They were some of the best plant and machine operators you could ever want,” he recalled.

“There was nothing they couldn’t do. We used them for the catwalks, the cable spinning, they got these fairly specialised techniques like that,” he said, snapping his fingers.

“Communication was a big challenge on that job to start with but we soon got something that worked with the help of the Gurkhas.”

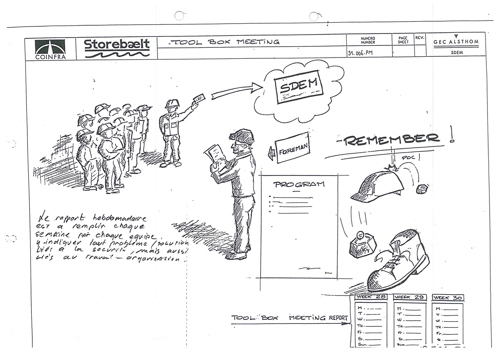

On his next job, the Storebaelt Bridge in Denmark, the language and cultural mix was even more complicated, with David and his small team drafted in by the main Italian-French contractor to complete cabling works prior to the Danish winter shutdown. A time sensitive job that simply couldn’t afford time lost to misunderstanding.

“While we had the Gurkhas in Hong Kong, in Denmark we brought in ski-lift installers and operators from the Alps to do the cable spinning. They were used to dealing with ropes and wires, just a different application of the same technology and skills.

“What was even more brilliant was we had a cartoonist – a friend of one of the engineers in the team - who did all the handbooks and method statements so we didn’t have to use words across the various nationalities.

No timestamp available

Storebaelt Bridge - cartoon 1

Download: 683KB Size: (1753 x 1240)px

No timestamp available

Storebaelt Bridge - cartoon 2

Download: 363.9KB Size: (1753 x 1240)px

No timestamp available

Storebaelt Bridge - cartoon 3

Download: 655.6KB Size: (1753 x 1240)px

“My first month there was spent describing what was going to be done and him translating that into cartoons - they were absolutely tremendous. I’ve still got a book of them. It worked a treat and between the pragmatic Scandinavians, the more volatile French and Italians and us, it turned into a remarkably cohesive team.

“That’s one of the great things about these jobs, working with a multi-cultural team and how you glue it together to achieve what you need to achieve. The Forth Replacement Crossing is exactly the same; we’ve got 27 nationalities on this job, which is typical for a job this size given the range of highly specialised skills required.”

Hard deadlines are a key theme in Climie’s career. The aforementioned Tsing Ma Bridge was one of a raft of projects connected with the new Hong Kong airport that contractors were racing hard to complete before the handover from the UK to China in 1997. “Contractually, it would have been enormously difficult to still be running through not just a Government change but a full national ownership change,” he said. “It really was the hardest of commercial deadlines and thankfully we met it. Fundamentally we’d be dealing with a totally different regime so if you had any outstanding claims or contractual issues… good luck with that!”

Major infrastructure projects are never built in isolation; they have to contend with the same world we all go about our everyday business in. And to paraphrase Bill Shankly, football isn’t life or death or even the transfer of Hong Kong sovereignty … it’s more important than that.

Earlier in his career, David oversaw the redevelopment of Notts County’s Meadow Lane ground in Nottingham. The club is the oldest professional football club in the world. Removal of standing terraces in the early 1990s was as a result of the Taylor Report into safer stadia following the Hillsborough tragedy.

Meadow Lane football stadium - Notts County

David, a St Johnstone fan from his early years growing up in Perth, was obviously well aware of the need to complete by a certain date: “We had to build three new seated stands, all in the close season. So we had cranes everywhere to get as much done as we could to then allow them to re-lay the pitch and be finished by the start of the new season. Obviously, a deadline you didn’t want to miss.”

Almost from day one, with a call out of the blue that took him to Cairo for over two years, David has experienced the short notice, on-the-spot nature of major infrastructure projects. A good job too, when it came to his next bridge project following the Tsing Ma and the Storebaelt.

“I took a call one day and was told I was being put forward as project manager for a new suspension bridge over the Yangtze River in China. That’s all I knew.

“So I flew to London, went straight to a meeting with Michael Heseltine, who was the UK Business Secretary at the time, and a delegation from China.

“There we were in posh Lancaster House and I’m introduced as the project manager for this major suspension bridge. All eyes were on me… and I had no briefing at all! The Chinese looked at me and there was some muttering. So I asked the translator about that and he said they were a bit worried I didn’t have any grey hair. I replied I was sure I’d be getting some soon. Which proved to be true.”

The next day he found himself on a plane to China to get into the final negotiations for the Jiangyin Bridge in Jiangsu province. The part-UK financed project was the fourth longest suspension bridge in the world at the time of opening and involved technology and knowledge transfer to the Chinese who could then go on to develop their infrastructure.

Jiangyin Bridge - China

But it was a project with particular – possibly unique – pressures.

“The bridge was one of 10 projects nominated to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the People’s Republic. This meant it had to be finished by October 1, 1999. It just so happened that President Jiang Zemin was born nearby… and he just happens to be an engineer. So, he had a double personal interest in the project. He visited three times and, put it this way, there was no doubt it was not going to be finished on time.

“The pressure was really on. Big eyes were watching so you better get it done right. In truth, it was a very technically challenging project, so much so that a year into it, it looked like it was going to be difficult to deliver on time.

“But we built a great team there, things improved and we eventually opened it on schedule as part of the celebrations.”

The legacy of the project, which at the time was creating the lowest downstream crossing of the Yangtze to connect the largely rural northern part of the province, has been profound.

David has returned to Jiangyin for 10 and 15 year anniversaries to reconnect with old colleagues from all over China.

“The city has doubled in size in that time, the whole place is booming. I’ve never seen so many Mercedes in one place, yet when I was there it was all bicycles and motorbikes. The city seems to have leapt forward 100 years in just 15. It really does show the power of infrastructure – if you build transport networks, investment follows.”

After successfully completing his work in China, David headed to the USA to lead Bechtel’s construction of the new eastbound Tacoma Narrows Bridge in Washington State. The location is iconic in the history of bridges, for all the wrong reasons. Many will have seen the footage of the original “Galloping Gertie” bridge collapsing into Puget Sound in 1940, not long after it was opened. Since then a replacement had been built but this was struggling to cope with the volume of modern traffic using it and a second bridge was ordered to share the traffic load.

Tacoma Narrows Bridge - Washington State

After around five years construction, the bridge opened in July 2007. Around this time, David’s mother passed away and after the best part of 25 years working around the globe, it was time to be close to home for a while. Returning to London with Bechtel, David was a key member of the bid team for a major widening project on the Panama Canal timed to coincide with the 100th anniversary of the famous shipping shortcut in 2014 – there can be few greater dream jobs for civil engineers. Understandably, he admits to some lingering frustration that the Bechtel bid lost out to another, especially as the job subsequently has run into issues and is still some way from completion.

He spent another year picking up special projects and troubleshooting work for Bechtel, including work on airports in Doha and Muscat. This was also when he visited the site of the Chernobyl nuclear disaster in the Ukraine to review the feasibility of a proposed confinement system for the abandoned plant, an enormous steel arch being constructed to seal in the concrete sarcophagus originally put in place to contain radiation following the accident.

Chernobyl nuclear confinement system - Ukraine

It was around this time that a flagship project for the Scottish Government was looking for a Project Director. The job, replacing and improving upon the Forth Road Bridge as the general road traffic link across the Forth, was more than just a return to Scotland. Two decades previously, David has already spent a year and a half working on a strengthening project for the Forth Road Bridge.

“I saw the post advertised and I thought maybe it is time to think about something different. Different for me was actually something close to home for a change. I grew up 30 miles up the road, went to university at Heriot Watt. I worked on the bridge right alongside it and have been building bridges for the last 25 years. It sounded pretty exciting. The right job, the right place, the right time. It was the biggest job in the UK, possibly Europe, at the time.”

Another difference was finally working on a cable stayed bridge after years of spinning the main cables for suspension bridges. But, fundamentally, the biggest difference was the role.

“It meant becoming a client for the first time, which would be a bit different. Challenges around the political, stakeholder and media engagement were not completely new to me, I had certainly witnessed them, but the comparative importance in my day-to-day role was new. On the other hand, it was felt helpful to have someone on the client side who had built one of these size of bridges before.”

The project still has many months left to go and you don’t have to be superstitious to understand the dangers of complacency on a project of this scale. However, so far David has been pleased with progress.

“The project is delivering all I hoped it would to date. We still have challenges to overcome but a lot less than we did at the start. The marine foundations were probably the biggest technical risk and to get through that without major incident is a big achievement.

“It’s an ambitious target: from starting in 2008 to be open by the end of 2016. The budget has been really well managed and the expectations of what you get for your money and how the risks have been managed and publicised.”

Having experienced how disparate nationalities, languages and cultures can come together successfully on previous projects, he is heartened by similar cohesion here.

David Climie - On site at the Queensferry Crossing

“I’m really pleased with the team that has been put together. Client, contractor and designer, the whole shooting match. There are a lot of very talented people on this project who are working well together across international and cultural boundaries. One of the best parts of the project has been how the fabrication in China has worked; it has gone tremendously well in terms of how it has been resourced and managed. It has also given the opportunity to use some of my former colleagues from Jiangyin Bridge days to form part of the EDT China team.

“I have a huge amount of respect for the contractor and how they do things. We’re co-located here, we talk to each other all the time. I think we’ve built very good relationships between client and contractor at all levels, lines of communication have stayed open. If those breakdown, things can go badly very quickly on jobs of this scale. But we put a lot of effort into that.

“Ultimately, because of the structure of the contract, what happens on site now is the contractor’s responsibility. But I believe we have a moral responsibility, without stepping over the line, to provide help, guidance, advice and challenge, for the good of the project. I see us and the talented team we have here as a resource for the contractor to draw from. After all, at the end of the day, the job is to build the bridge safely, to the right quality and on time. That’s the fundamental point of us all being here.”

Infrastructure projects do not afford much time for reflection, it’s only after the job has been completed successfully do most engineers allow themselves the luxury of pride. But the Forth Bridges surely hold something special for an engineer, especially one from Scotland.

“It is a unique situation with the other bridges and I do get a personal thrill from being involved in a new bridge to stand alongside them. And, of course, it’s nice to do something to contribute to Scotland in the long term.

“But to be honest the thing that gives me the biggest buzz about it is more personal than that. I look at my Dad, who is in his eighties and still lives up in Perth, and my nephew who is 9 who lives in Edinburgh. Both of them are as excited by the bridge as I am. My nephew can go to school and he’s proud to say his uncle works on it. Similarly with my Dad, he goes to the golf club or his Probus club meeting and people talk about it to him. It’s great to be able to go back home and, to a degree there’s an element of local guy made good. I get a warm feeling from that.”