Open to buses, taxis, and motorcycles up to 125cc. East footpath open to cyclists and pedestrians. West footpath closed for essential maintenance.

Access RestrictionsBlog: The Forth Bridge - Digitally Documenting an Icon

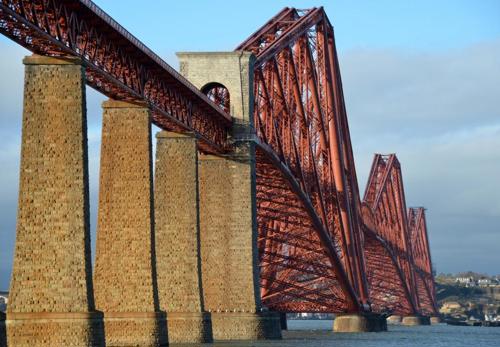

Dr Miles Oglethorpe - Head of Industrial Heritage, Historic Environment ScotlandFor many people, the Forth Bridge is such a major icon that they think it has always been a World Heritage site. However, this was not the case until 5 July 2015 when UNESCO’s World Heritage Committee, passed a motion accepting the nomination and inscribing the Bridge onto the World Heritage list. At that moment, Scotland gained its sixth World Heritage site, and the UK its first successful nomination since 2009.

World Heritage is often misunderstood, with little understanding of the complex processes and strict demands that it carries with it. For the nomination team, based in Historic Scotland, the task was made a lot easier by the fact that the nominated site was only a single entity – a bridge, albeit a very big one. Other nominations often have a large number of component parts, sometimes scattered across a region, a country or several countries. We were also very fortunate to have a group of partners who were able to work closely during the nomination process, under the banner of the Forth Bridges Forum, led by Transport Scotland.

Unlike in the early years, all World Heritage nominations now have to have a ‘Management Plan’ that sits alongside the ‘Nomination Document’, its function being to demonstrate to UNESCO and its expert assessors that the nominated site is being looked after properly, and is not in danger of falling into decay or at risk from rampant development. The nightmare scenario is for a site to be inscribed and then to be included on the ‘World Heritage at Risk’ list immediately afterwards. Equally, UNESCO demands regular reports on the condition of sites that have been inscribed, so regular monitoring and reporting is mandatory part of having a World Heritage Site.

Through the Scottish Ten project, we learned that the 3D laser scanning can be immensely valuable, providing a baseline record and also the basis of virtual access as well as educational and interpretation digital resources. This proved to be the case for Rani ki Vav, which was inscribed in 2014. The success of Rani ki Vav was a major motivation for 3D laser scanning the Forth Bridge, and was listed as an action within the Management Plan. In addition to supporting monitoring and conservation, there are so many other ways in which we will be able to use the Forth Bridge data in the future, not least virtual access, site induction and health & safety, engineering calculations, management of the setting of the Bridge, and even games. It couldn’t be more exciting, and is especially pleasing as, above all, it will allow us to share with the world in great detail the wonders of this extraordinary engineering marvel – something that UNESCO is anxious to see done for all World Heritage sites.

Miles Oglethorpe